Insert Headline

Insert text here.

In 1764, the British Parliament passed the American Revenue Act, commonly known as the Sugar Act of 1764. This tax went into effect on September 1st 1764. In theory, the Sugar Act of 1764 was simply a revision of the Molasses Act of 1733 In practice it was a gross underestimation of New England’s strong attachment to their profits and fierce desire for self-determination.

The Sugar Act sought to regulate the sugar trade and to capitalize on the widespread smuggling of sugar and molasses in the New England colonies. The goal was to raise revenue to pay off Britain’s war debt and to fund garrisons in the American colonies. However, arriving so soon after colonial opposition to the Writs of Assistance and “taxation without representation”, the Sugar Act of 1764 instead helped stoke the fires of New England’s discontent.

Insert Headline

Insert text here.

The Sugar Act of 1764:

A Stepping Stone on the Road to Revolution

by David J Samuels | November 20, 2024

Office: 10:00 am - 5:00pm

1 (857) 277-0121

The Molasses Act of 1733 was aimed at protecting British economic interests, particularly the sugar plantation owners in the British West Indies. By imposing a tax of 6 pence per gallon on molasses imported from non-British colonies, it sought to discourage the importation of cheaper, higher-quality molasses from places like the French and Dutch West Indies. However, the act proved largely ineffective. Instead of paying the tax, New England merchants found it more economical to bribe customs officials in Boston, allowing them to continue smuggling molasses at a lower cost. The British government, however, preoccupied with other matters, put little effort into enforcing the Molasses Act and therefore collected very little in terms of revenue and nothing was done to discourage smuggling. This left New England merchants the ability to continue on as they had been, meaning they could smuggle to their heart’s content with little to no interference from the government in England.

The Molasses Act of 1733: The Sugar Act 1.0

The Sugar Act of 1764: Grenville Misjudges New England Merchants

The tax reduction was accompanied by a new determination to enforce the tax and combat smuggling. Smuggling was a time honored tradition in New England. George Grenville sought to change this.

To ensure compliance, Grenville instituted a number of important improvements to the way the collection of taxes was handled in the British American colonies. Prior to the Sugar Act of 1764, colonial customs officials were often from England and many chose to never set foot in the colonies. It was common for these men to hire a local to act as their agent. Grenville put an end to this. Customs officials were now required to reside in the colonies and perform their duties in person, rather than appointing local agents. Ship inspection and registration procedures were tightened, and legal recourse for merchants was severely limited. Any disputes over seized cargoes had to be heard in a newly established Vice-Admiralty Court in Halifax, Nova Scotia, forcing merchants to travel great distances to contest the seizures.

Whereas New England merchants were largely able to ignore the Molasses Act of 1733, George Grenville sought to force them to pay up.

By the mid-1700s, New England merchants were importing about 1.5 million gallons of molasses annually, much of it smuggled from non-British colonies. This molasses was crucial to the colonial economy, as it was distilled into rum, which was then traded for enslaved Africans and other goods. The trade in rum, molasses, and enslaved people formed a key part of the so-called "triangular trade" that linked New England, Africa, the West Indies, South America, and the Southern colonies. The profits from this trade were enormous. A gallon of molasses, costing about 16 pence in the West Indies, could be distilled into rum and sold for around 192 pence. New England merchants, by avoiding the 6 pence per gallon tax through smuggling, maximized their profits, collectively earning around 1.2 million pounds sterling annually. These profits underpinned not just the rum trade, but also the trade in enslaved Africans and Indigenous Americans, who were forcibly exchanged in a brutal system that linked the economies of Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

The Sugar and Molasses Trade

The Sugar Act of 1764 was met with resistance from the colonies, New England in particular. Merchants argued that the act threatened not only their profits but also the broader economy of the colonies, especially the slave trade, which depended on molasses. Furthermore, they objected to the tax as a violation of their rights as Englishmen, echoing the arguments of James Otis against the Writs of Assistance.

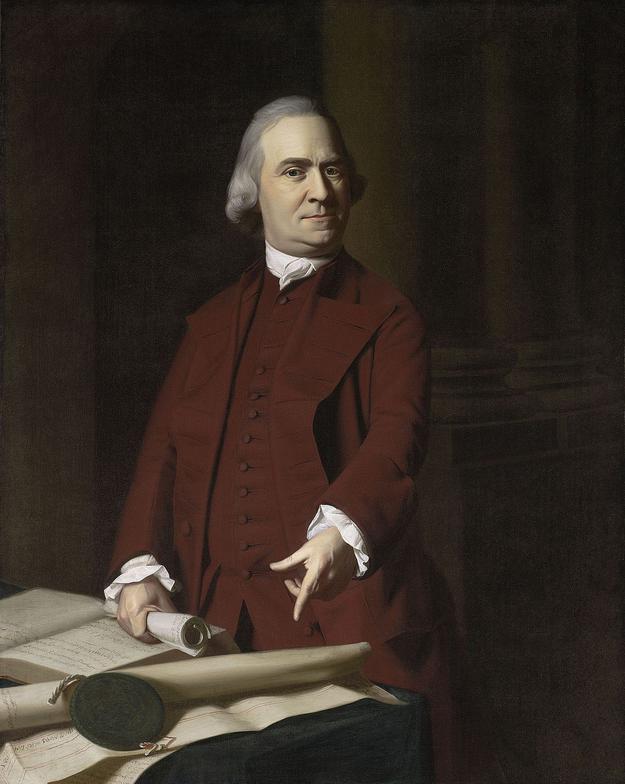

Samuel Adams, then a member of the Boston Town Meeting, articulated this resistance by condemning "taxation without representation" in his instructions to Boston’s Representatives to the Massachusetts General Court. He argued that the Sugar Act violated the colonies' rights to self-governance and reduced them to a state of unfreedom.

Resistance to the Sugar Act of 1764

"For if our Trade may be taxed why not our Lands? Why not the Produce of our Lands and every thing we possess or make use of? We apprehend this annihilates our Charter Right to govern and tax ourselves– it strikes at our British Privileges, which as we have never forfeited them, we hold in common with our Fellow Subjects who are Natives of Britain: If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without us having legal Representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of Free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?”

Samuel Adams:

The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 were both repealed around the same time by the Revenue Act of 1766. Passed in Parliament in 1767, the Revenue Act of 1766 is more commonly known as the Townshend Act. This new law taxed paint, paper, glass, lead, and tea. The Townshend Act, passed alongside the Free Port Act of 1766, acknowledged that British sugar plantations in the West Indies could not meet domestic demand. The Free Port Act of 1766 opened ports in the British colonies of Jamaica and Dominica to the importation of foreign sugar, where New England merchants could access it from within the British Empire.

Repeal of the Sugar Act of 1764

Conclusion

Sources:

Patriots by AJ Langguth

John Hancock: Merchant King & American Patriot by Harlow Giles Unger

The Samuel Adams Heritage Society

Unfreedom by Jared Hardesty

The Sugar Act of 1764 was an attempt by British Prime Minister George Grenville to raise revenue from New England’s trade in sugar and molasses. He designed the tax to cost only one more pence per gallon of molasses than New England’s merchants were paying customs officers in bribes when they smuggled foreign molasses and sugar. Though he had cut the tax on foreign molasses and sugar from the Molasses Act of 1733 in half, Grenville intended this tax to be enforced, which New England merchants refused to accept.

Grenville believed New England merchants would agree to pay the small increase in their cost of doing business. However, Grenville grossly underestimated their opposition to “taxation without representation” and, perhaps more importantly, their attachment to their profit margins. Instead of increasing revenue, Grenville gave Samuel Adams a moment to shine and a platform from which to increase his popularity. Adams would go on to use this increased popularity to march the British American colonies towards revolution and independence.